Atari, India. Thursday 27th April 2023

The Atari/Wagah border was due to open at 10 a.m. While we waited at a café across the road, the taxi driver and I drank chai. At 10:15 the gates opened and I was off, heading for Pakistan, country number thirty three on my trip. This border is the only one between the two countries.

Getting out of India was a bit slow because they seemed to want to check my passport every ten paces. I gave my luggage to an elderly Sikh man with a luggage trolley, who trundled along behind me like a faithful pack horse. There were signs advising me that the standard fee for these guys was INR200. That seemed fair enough to me.

I had to speak to a medical woman who wanted to know whether I was returning to India. I told her yes, and before I’d managed to close my mouth she’d put a polio booster into it and given me a card to confirm it. I then got on a bus and was taken to the area in front of the gate, where I’d watched the closing ceremony the previous evening. One last passport check and I was through the gate.

A bit quicker through the Pak formalities. Immigration checked my visa letter then put the entry stamp onto that rather than in my passport. Was there a reason for this? Unknown. Meanwhile the Pak version of the elderly Sikh guy had my luggage on his trolley and once clear of formalities, we trundled out to where the taxis park. I teamed up with a young British guy and we shared the fare into Lahore. Everything went smoothly at this well organised border crossing, with no sign of the histrionics of the previous evening’s gate closing ceremony.

I’d booked into a hostel that was near to the bike shop area. My Indian friend Jay had introduced me to one of his Face Book friends who was going to help me buy a bike. The hostel was also close to where he worked. Salman is a bit of a big wheel on the biking scene there. Just to remind you, there was no way of getting my Indian registered RE Himalayan across the border. So a new bike had to be bought, then sold again when I was finished with it.

Once I’d dragged my luggage up the fifty – FIFTY! – steps from the street to the top floor. I was able to settle into my room and relax. Sajeed, the owner of the hostel, took me out to get a SIM. This could only be done at an outlet of the Teleco, rather than at one of the small phone shops. I bought a post-paid card, which Sajeed said was cheaper and easier, but paid ahead for two months. Next job was an ATM for some ready cash, with a withdrawal fee of less than £2. I was now starting to feel organised. There was a handy pizza joint nearby, very useful while I worked out what my eating options would be.

One thing I immediately liked about Pakistan was that chai arrived in larger portions and in actual cups, unlike India’s tiny paper cups.

First impressions of Pakistan? Much the same as India really. The people look the same and the traffic is just as bad. I expected to see lots of women wearing hi-jabs but I didn’t. That was mostly because I didn’t see many women. The most common dress among men was the Kameez Shalwar, which is an outfit consisting of a mid thigh length, long sleeved shirt, and a pair of very loose fitting trousers. They could be smart or ordinary and are designed to be comfortable in the often very hot weather. They’re always associated with Islamic countries, especially Pakistan and Afghanistan, and although the style originated in that area it pre-dates Islam by five hundred years or more.

Late the next morning I walked up to meet Salman at his business premises. He imports and supplies various chemicals, especially powdered Portland stone and calcium carbonate. This equates to a very dusty shop, with white powder everywhere. We went across to the office where I met his business partner,Mr Jass. He sent out for some lunch and we discussed various topics while we ate, partition in particular. He felt it had been a very bad thing and blamed the politicians of the time for not settling on a system with autonomous Muslim areas rather than divide the country. I’ve covered this topic before so I won’t revisit it, but I will say that many older people I spoke to regretted it. Younger people simply regretted that the two governments were at loggerheads, thereby restricting their ability to mingle with their natural friends across the border.

Salman had been talking to people in the various bike shops and after lunch a guy came over with a very nice looking Honda CB125. It was almost new, with 3,300 kms on the clock and had not even been registered yet. The ubiquitous bike in Pakistan is the Honda CG125, or its 70cc smaller brother. And they were all painted red. I was pleased with the CB125 because it had a disc front brake and a 15 litre tank, as against the drum brake and 10 litre tank of the CG model. Long story short, I bought it.

Salman negotiated a price of 3.25 lac rupees. A new one cost 3,65 lac and over the weekend (this was Friday) Honda increased the prices of all their bikes by 0.3 lac. So quite a good saving. I’m sure you’ve read the previous sentences wondering what all this means. One lac means 100,000. There’s 3.5 Pakistani Rupees (PKR) to the GBP. The bike therefore cost £950. Over the next few days I bought all sorts of extras for the bike and spent almost £1,000 in total. It may seem a lot but I knew I’d get a good price for this bike when I sold it again. Salman, meanwhile, got the bike registered in his name.

He was going away for the weekend and although he now possessed the bike, he’d locked it securely away until I had the cash to pay for it. He very kindly invited me to come away with him and his wife but I declined. I had too many things to organise.

Later that day I got a message from a guy named Malik, who’d originally contacted me way back in November 2019, when I’d first arrived in India. He’d become aware that I’d arrived in his city and he wanted to meet me. He and his friend Aseeb came to the hostel later and we went for something to eat. They were on one bike and I squeezed on there with them while we zoomed through the streets to one of the busy eating areas. I was beginning to feel like a local, squashed between the two of them on the seat.

Like all Asian cities, Lahore has its eating areas, full of cafés, street stalls and chai houses. Malik chose a good one and I enjoyed some not-too-spicy chicken and chapati while we chatted. I liked the idea of the dish of curd that was delivered before the food. If you’ve never tried it, fresh set yoghurt is the closest thing to it. In India it’s mostly served with food, in Pakistan it often comes as a starter as well. But here I discovered a common theme, which was that eating places rarely served hot drinks. So we had to go somewhere else for the essential cup of “chai no cheeni”, or tea with no sugar. I’d already noticed, when walking around, that the city lacked the plethora of chai stalls commonly found in India.

This whole area was busy with diners, hawkers and serving staff rushing around. It was already 10 p.m. and things looked to be just getting going. We chatted about my plans, with Malik giving me lots of safety advise for riding in Pak. He also said he’d work out a list of places to go and people to meet. Just what I needed.

Next day I decided to be a tourist and walked up to visit the old fort. It’s located in a nice park, which has a variety of family attractions and places to eat. It was a bit of a hike but I didn’t mind. It gave me a chance to get the feel for the city streets that you’d never get that from riding through.

The fort was built by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in the 16th century, on the site of older fortifications. It was totally rebuilt during the 18th century, by a later Mughal emperor, so what I saw dated from that time. The buildings were based on Islamic and Hindu themes. I was a bit puzzled by the Gurdwara outside the fort but it’s a result of the forty years of Sikh rule that came after the fall of the Mughal empires. The East India Company fought and defeated the Sikhs in 1843 and took it over, using it as a storage and administrative base.

It cost me 500 rupees to get in, the same ‘foreigner’ price as I was used to paying in India. But this time I didn’t mind. 500 INR is 5 GBP. 500 PKR is a measly 1.5 GBP. I was approached by the inevitable guide who asked for 1,500 PKR. I said “No thanks”. After a pause he brought the price down to 1,000 PKR. I was happy to accept that.

He was a well educated young guy, who spoke excellent English and did a great job of showing me the various buildings and their purposes. One thing he told me was that the Mughals, who I’d assumed had invaded India from Arabia, actually came from Central Asia and Persia. This accounts for the Persian etymology of many South Asian words. The tour was very enjoyable so when we parted company I gave him the 1,500 PKR he’d originally asked for. I’d told him about the bike I was buying and he offered to help me sell it when I came back. Both Salman and Malik had made the same offer and I said to my guide what I’d told them – the best offer gets the deal. If you want to know more about the fort, the Wiki link is here.

I collected the bike from Salman the day after his weekend away. The Monday had been May Day and there were workers meetings in the main road by the hostel. I walked down there to see what was going on and found speakers on open topped buses and people sitting around on the carpeted road, enjoying the speeches and their family picnics. A fascinating scene. I joined in the chanting at one point and got cheered by some people near me for doing so. Needless to say I’ve no idea what it was all about but you’ll always find me on the side of the workers.

I had a list of things I needed for the bike and Malik generously gave his time to help me. Most important was a pair of panniers for carrying all the bits and bobs I needed, such as padlocks and tools, and also to store my rain coat. My bag was going to be strapped to the seat and onto a rack that we’d bought and then had extended. One of Malik’s friends, Hafeez, had a very busy repair business and he got the rack extended for me. He also did a couple of electrical jobs, such as installing a USB charger for my phone. I spent ages running around the city, with Malik on the back of the bike, going to various suppliers and slowly getting used to the heel/toe gear change – a new feature to me.

The location of this workshop was down a side alley. Going down it you suddenly come to an area of small, busy workshops, with bikes being worked on in the street (a dead end, fortunately) and each of them helping the other out. The alteration of the rack was undertaken by a small fabricators round the corner. I was worried that the securing straps were going to wear the paint on the side panels so Hafeez arranged for them to be covered in clear plastic, also carried out at a place nearby. Next to this business was a very well equipped workshop that reconditioned engine parts. Rebores, all sorts of bearing replacement and cylinder head repair. Anyone who owned a small Japanese bike in the 70s/80s/90s will be well aware of the carnage caused to the cylinder head if there wasn’t enough oil. This damage requires skilled repair and I was thinking how popular this business must be. The guy running the shop was very welcoming and made me feel a bit like royalty.

We visited one of Maliks friends for lunch. He ran a business that seemed to focus on selling classic vehicles. In pride of place was his 1983 Land Rover 110 Long Wheelbase, with a petrol engine. He’s a very well travelled man, including on adventure motorbikes. He’d been to the UK too. I found this a common theme in Pakistan. Many people I met had travelled or worked in the UK and almost everyone had a friend or relative living there.

Malik had given me a list of places to visit and I sat down one evening to make a plan, with Malik’s help. In the north of Pak there’s a clear division between the eastern and the western side of the mountains. Plenty of north/south roads but fewer that go east west, once you get north of the Grand Trunk Road. So I worked out a route that looped north, then south on the eastern side (closest to India), then did the same for the western side (closest to Afghanistan). I intended to do the western side first but I was later talked out of that because the winter snows would still be holding sway. Two ‘must see’ places on my list were the famous Karakorum Highway, which led up to the Chinese border, and the infamous Khyber Pass, leading to the Afghan border. The KKH was famous among travellers and the Khyber Pass was famous among anyone who’d ever tried, and inevitably failed, to conquer Afghanistan.

On the evening before I left Malik came round and we went to the same area to eat again. Afterwards we went back to the workshop for a bit of a biker meet. Lots of new faces to be introduced to. Then we went on the Old City Wall Ride. This is a bit of weekend fun and involved chasing through the streets of the old city. I was on the back of Malik’s bike, hanging on as best I could. We met more people there and I had a look at the old buildings around. I got into a political discussion with one guy, who believed that everyone in Britain only saw Pakistanis as terrorists. I assured him that wasn’t the case. He took me for a walk around the local streets, showing me a few out of the way places of interest.

When we got back, glory be, chai arrived. I was gasping! Hafeez had been busy and had made up some certificates saying that xxxx had completed the Old City Wall Ride on that date and had met me! My job was to write in the person’s name and autograph it for them. A delightful bit of old flannel, which I really liked. One of the people that had arrived was a young woman, on her own bike, and looking very much the part in her riding gear. Pakistan doesn’t hold women back in the way that some Islamic countries do, but she was still an unusual sight. Social activity tends to take place late in the evening there and I was very pleased when I was able to get back to my bed.

Malik had arranged for me to meet one of his friends at Khewra Salt Mines, only 260kms from Lahore. I was on the road by 9 a.m., enjoying the fact that the traffic was quiet. Despite all the warnings from Malik and Salman, I never found Pak drivers or riders any worse than their Indian brethren. In fact very often they were better. Neither of them quite understood the quality of the training I’d received on India’s roads. I feared nothing!

I filled the bike up and was pleased when it took 15 litres. I knew that would give me a good range. Malik had said to always fill up at 300kms but I actually had a range of over 550kms, with a consumption of close to 40kms per litre. Very handy.

The journey involved crossing Victoria Bridge, a place that was on my visit list. It’s a 19th century railway bridge but with a pedestrian and bike track running along either side. A little bit of a twisty path to get onto it, then a nice ride across the wide river. Cars had to take a nearby ferry, big enough for about four of them. The Jhelum River sits in a wide plain, running up to the high ridges of the foothills, about 15kms away. It became a bit of a directional marker later on because it could often be seen from some of the places I went to.

I met Tanveer and his friend Wassin at the salt mines. We went inside, with me paying for them. Their price was local, too small to remember. My price was the foreigner rate of 20USD! That’s robbery as far as I’m concerned. The question is, was it worth it? We got a small train into the interior, a short enough distance to walk if you felt like it. There were various salt sculptures to look at, most of them very pretty. What I really liked was that the salt came in a variety of shades of pink and orange. Blocks of it were made into miniature buildings, or similar, then illuminated. They looked very nice indeed. Worth $20? No, definitely not. Maybe half of that. I’d been to a salt mine in Poland where the accessible area was vastly bigger and the sculptures far more varied, albeit not quite as pretty. Khewra was a great place to visit if you don’t mind the cost.

I stayed at Tanveer’s house that night and met his family. I enjoyed some nice food and he showed me some photos of his own travels. Out of that came a few more suggestions as to places to visit. Later on we went to the house of one of his friends, walking through the village streets. There was a group of people there playing a board game that involved moving pieces around and taking pieces off the opponents. It was fast moving and looked like good fun. I didn’t find out what it was called but it looked the same as Ludo. Very competitive and noisy though.

In the morning we went to a place called Kusak Fort. The fort isn’t on the map and is pretty much a ruin. We had to scramble up a steep goat track to get to it. Not much fun in riding gear. There was an old Sikh Temple up there along with the ruins. Hard work for not much, but the view was great. I could look across the plain, which ran all the way down to the coast, and could see the Victoria Bridge too.

Our next visit was to Katas Raj Temple Complex, a collection of Hindu buildings, but also including a Gurdwara from when the Sikhs ruled the area. Sadly, some of the Hindu buildings had been vandalised in an act of revenge following the destruction of a mosque at Ayodya, India, in 1992. Stupidity in action. At this point we met up with another of Malik’s friends, Ali. He’d brought three others with him. Ali seemed to see his role as shepherding me around, with instructions to “come” and “go there”. I didn’t particularly care as I’m sure he meant well. Tanveer was snapping away endlessly with his big Nikon. Everyone had cameras so I spent much of my time acting the fool as we walked around, as many of the photos had me in them. But it felt eerie to be there. A sense of history now gone, and since partition, never to return.

We went for lunch then hit the road and went to several other places. I was impressed by how they knew where these places were as they all seemed to be out in the wilds, often down dirt tracks. Here’s a list, in order of visit.

Malot Fort; a 10th century building in the salt producing area. Its architecture harks back to that of the Greeks that occupied this area, from when Alexander The Great was in charge.

Katas Raja; dating from the 3rd century, it’s a complex of Buddhist and Hindu buildings that surround a sacred pond.

Dalwal Bungalow; an old British customs post located on one of the ancient salt roads.

Malkana temple; there are two dilapidated buildings here. A temple for men and one for women. The area was abandoned after partition and the temples left to nature. There is a large banyan tree there, looking as ancient and gnarled as any old priest could ever be.

Malot mandir; a pair of temples built at the same time and in the same style as Malot Fort. They’re an identical pair sitting on top of a hill with a splendid view of the surrounding area. Unfortunately coal and cement mining have undermined them and made them liable to collapse. Pakistani and Indian architects have worked together to preserve many of the Hindu structures in the area and consideration is being given to moving these temples to a safer area.

After that long and very busy day, I was going to be staying with a guy named Chaudhray Tauqeer who, it turned out, lived a long way away from where we were. The group progressed towards the more populated areas and people dropped out as they came near to where they lived. We stopped for food and then, later on, for chai. Eventually we reached Tauqeer’s house, set inside a small compound in a small village off the main road. The bike had handled all the rough dirt roads amazingly well, and the faster riding too. I was very impressed with it.

Tauqeer is a lovely man who used to be a commando. He was pensioned off following pancreas problems, from which he still suffers. He’d recently been in hospital and I was a bit concerned that he might have worsened his situation by coming out for such a long day. But he’s tough as well as friendly and assured me he was perfectly alright. After some chai I can happily confess that I was very glad to get to bed.

The plan for the next day was to ride to Rawalpindi but before we left we rode around the village to meet a variety of Tauqeer’s relatives. Brother, cousin and a couple of grandfathers. One of them is 100 years old and the other is 120. I’m not sure I quite believe that, to be honest. It seems rather implausible.

When we reached the city we went to visit Azur, a guy in his seventies. He’s an experienced traveller and had just returned from Oman. Chai was drunk. While I was parking the bike I managed to let it fall over against a wall, which broke the mirror glass. I didn’t expect it to be too difficult to replace in a land where Honda reigns supreme.

After that we rode to the hotel where Tarqeer worked as a night manager.On the way we passed a disturbance where the police and a large crowd had been at loggerheads. There were pieces of stone scattered about and a couple of burning tyres. We passed through some smoke, which I assumed to be from the tyres but turned out to be tear gas. My god that stuff is dreadful. My eyes were stinging so much I couldn’t keep them open. It certainly lives up to its name. At the hotel we were able to rinse our eyes out but the effect remained for a long time. We heard later that the protests related to Imran Khan’s arrest as he came out of court.

Tauqeer had only come to collect his medicines but we had some lunch there, and chai, of course. We went to find a replacement mirror and had to buy a pair at the massive price of PKR600 – less than £2! We’d heard that the main road was open again after the protests so we headed out of the city. Tauqeer was going home and I was heading west, to Wah, to meet another biker friend.

Well “open” didn’t really cut it. The road may well have been open somewhere the other side of the monumental traffic jam we came across, but we didn’t get there. It seemed as if all the traffic was being funnelled down into a narrow roadway and the jam was MASSIVE!. We tried all the tricks that usually work. Riding along the pavement; across garage and shop forecourts; over traffic islands and the centre reservations. None of it worked. In the end we turned back, which in itself was a major challenge. None of the hotels had a room for me so I ended up staying at Azur’s flat. The mattress on the floor was comfortable enough, the only problem being that he smokes. But I was happy to live with that just for a night.

Mango juice for breakfast (delicious!), fitted the new mirrors then went to the hotel for breakfast. Tuaqeer was going to the hospital for check-ups, I headed out of the city, along the Grand Trunk Road (GTR) to Wah. I was heading west, towards the Khyber pass, but was going to meet Soihil, one of Malik’s friends.

As a traveller I’m always fascinated by roads: how they got there; where they go to; their purpose; what impact they’ve had on the environment through which they run. Since mankind first started trading roads have been a defining feature of the landscape. Ancient routes, such as the Silk Road, have followed the contours of the land. Modern routes, such as trunk roads and motorways, have altered it. So what is the GTR all about?

The GTR.

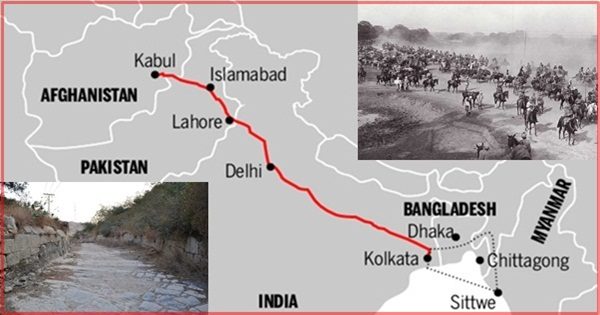

Firstly, it’s long. 2,400kms (1,500 miles). It runs from Teknaf, on the Bangladesh/Myanmar border, all the way to Kabul. It passes through Chittagong, Dhaka, Kolkata, Lucknow, Delhi, Amritsar, Rawalpindi and Peshawar. So you might immediately think, “Hang on, those places all used to be part of the British Raj so they must have built it. Good, but incorrect, logic. It follows an ancient route called Uttarapatha, and was first set out in the the 3rd century BCE. It’s been there quite some time! The British hugely improved it, of course, and gave it a metalled surface.

Rudyard Kipling said of it, “Look! Look again! And chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnias, pilgrims – and potters – all the world going and coming. It is to me as a river from which I am withdrawn like a log after a flood. And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India’s traffic for fifteen hundred miles – such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world.”

And that sums up the romance that feeds into me when I travel all roads. Wiki link for the GTR here.

Of course the reality is a wide dual carriageway, crowded with lumbering trucks, their smoke and dust, cars, bikes, businesses alongside and general comings and goings. Pretty much what I’d been used to around these parts. But still, it’s the flow that’s the thing.

I met Soihil and he took me to a place that serves as a warehouse for his medical supply business and also a biker base. There was a lounging area, with some mattresses to sleep on and a kitchen and wash room. After some lunch he took me to see some local sights. The first was an ancient stupa, looking remarkably good for its age. Next was the Taxila museum and an ancient town. This city was founded around 1,000BCE but was conquered by Alexander The Great in 326BCE. The area is famous for its Greek influenced architecture – seen at some of the sites I’d visited a few days before. The town we went to was based on a Greek layout. Up until then I had never realised the Greeks had travelled this far east.

Soihil was out all evening so I was able to catch up on the internet, having been deprived of it due to the troubles in Rawalpindi. He talked me out of going to Khyber because of the weather related road closures. He helped me to revise my route to go east and north before coming west again. We went to a café for breakfast before I said goodbye to Soihil and headed east, then turned north. I came onto the N35 which, after a bit of wandering about, became the Karakorum Highway. I was on my way to the mountains!

Why did I write the title to this blog post in that style? To remind me to explain that Pakistan is an acronym. It was first coined by Choudhry Rahmat Ali, A Pakistan Movement activist, in 1933. It relates to the a four main areas of the country: Punjab, Afghania, Khyber and Indus Sindh. The ‘stan’ part is from Balochistan and is an ancient Persian word meaning ‘land, or place of’. He also suggested Banglastan for the Muslim areas of Bengal. One thing demonstrated by this was that the Idea of a separate Muslim area or country had been around for quite a while before Partition.

Fascinating stuff, Geoff. Great pics, too!

LikeLike

Thanks Jan. There’s much more to come. 🙂

LikeLike

👍

LikeLike